Investigating Coral Tumours in Oman: Is the Microbiome Changing, or Are Corals Just Growing Strange Architecture?

Written by: Malaak Al Lawati

Based on research led by Dr Thinesh Thangadurai from the Department of Marine Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2025.107616

Coral reefs are vital ecosystems that support millions of people worldwide, but they are increasingly under siege from diseases that cause widespread decline and mortality. One globally reported condition is known as Coral Growth Anomaly (GA).

A GA is basically a coral tumor, characterized by abnormal skeletal growths that profoundly alter the coral structure. Imagine if your house suddenly started growing weird concrete lumps that messed up the plumbing and made the windows stop working. The growth anomaly distorts the coral skeleton, leaving less space for each polyp and its symbionts to photosynthesize. This cramped structure produces abnormal tentacles, weakens energy production, and can eventually lead to coral mortality — a condition reported in more than thirty stony coral species worldwide.

Coral Growth Anomaly in Acropora pharaonis. Photo by: Greta Abey

The exact cause of GAs (etiology) remains a mystery, and that is what Dr Thinesh Thangaduri from Sultan Qaboos University, along with Professor Sergey Dobretsov, UNESCO Chair in Marine Biotechnology and Dr Greta Aeby from Qatar University, sought to learn more about.

In the first study to establish baseline information on bacterial communities in Acropora from Omani reefs, Thinesh and his team began to uncover the microbial dynamics associated with these puzzling growths.

The Coral-Microbe Ecosystem

Corals are complex ecosystems with an entire community of microorganisms living inside their tissues. This community, known as the microbiome, maintains key life processes, including nutrient cycling, stress response, and disease defense. Essentially, they keep the coral healthy.

Thinesh and his team questioned whether the microorganism community and abundance differed between healthy and diseased coral tissues. Most importantly, did GA tissues host specific disease-causing pathogens?

To study this, the team went straight to the source: the Inner Island of Bandar Al-Khairan, where a higher prevalence of GAs had been observed. There they collected samples of healthy and diseased Acropora pharaonis tissues, as well as surrounding seawater (just in case the source of the trouble was swimming by), across two seasons: fall and summer.

Next-generation sequencing revealed an unexpected pattern—a microbial contradiction. Instead of showing a major shift in overall community richness, the corals maintained similar diversity between healthy and diseased tissues. The key differences emerged only in the abundance of specific bacterial taxa, which shifted significantly despite the stable richness.

They Key Actors

Overall, they found that the bacterial community was primarily composed of the phylum Proteobacteria (about 60.8%), followed by Firmicutes and Bacteroidota. Among all taxa, one genus emerged as the central microbial partner: Endozoicomonas.

Endozoicomonas were the single most abundant bacterial genus across all samples, representing 34.1% of the total bacterial community, followed by Aeromonas (6.2%) and Synechococcus (4.9%). It remained the dominant genus in both healthy and GA impacted tissues, though its abundance declined noticeably in the diseased tissues.

The persistence of Endozoicomonas in both healthy and affected corals, and its near absence in the surrounding seawater, suggests that the corals actively maintain this association. This genus is widely recognized as a core member of the coral microbiome, with potential functional roles in nutrient exchange and sulfur cycling that contribute to host fitness.

In contrast, the genus Fulvivirga was enriched in diseased GA tissues compared to healthy tissues. Members of the Flavobacteriaceae family, including Fulvivirga, are known polysaccharide degraders, suggesting that their increased presence may reflect localized tissue degradation associated with the growth anomaly.

Setting the Baseline and Future Directions

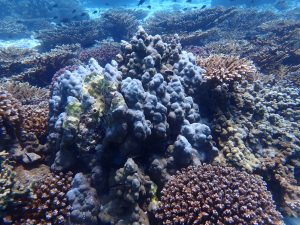

Coral Reef at Daymaniyat Islands, Oman. Photo by Dr Melissa Duncan Schiele

This study sets a critical baseline for understanding Acropora microbiomes in Oman.

The crucial finding was that Thinesh and his team found no evidence of any potential pathogens like Vibrio spp. or Flavobacteriales in the Acropora GA tissue. This suggests that these well-known pathogens are probably not behind this coral growth anomaly, suggesting they are likely not the cause of this specific growth anomaly.

Instead, shifts in bacterial abundance, like a drop in beneficial Endozoicomonas, are likely a consequence of the disease.

The way that GAs impact the physical structure of corals, including reducing polyp size, abnormal tentacles and thinner tissue layer, likely make it a difficult environment for bacterial growth and nutrient availability, which the coral needs. In other words, the corals are trying hard to maintain health, but the structural flaws of the GA are making survival hard, resulting in lower microbial abundance.

The next step is to stop looking at who is there and start looking at what they are doing (using metagenomic and meta-transcriptomic analyses). The functional activity of these microorganisms needs to be studied to understand their impact. Additionally, non-bacterial suspects like viruses and fungi must also be looked at to complete this puzzle.